Remote Sensing

- (From NASA) Remote Sensing is the acquiring of information from a distance. NASA observes Earth and other planetary bodies via remote sensors on satellites and aircraft that detect and record reflected or emitted energy. Remote sensors, which provide a global perspective and a wealth of data about Earth systems, enable data-informed decision making based on the current and future state of our planet.

Observing with the Electromagnetic Spectrum

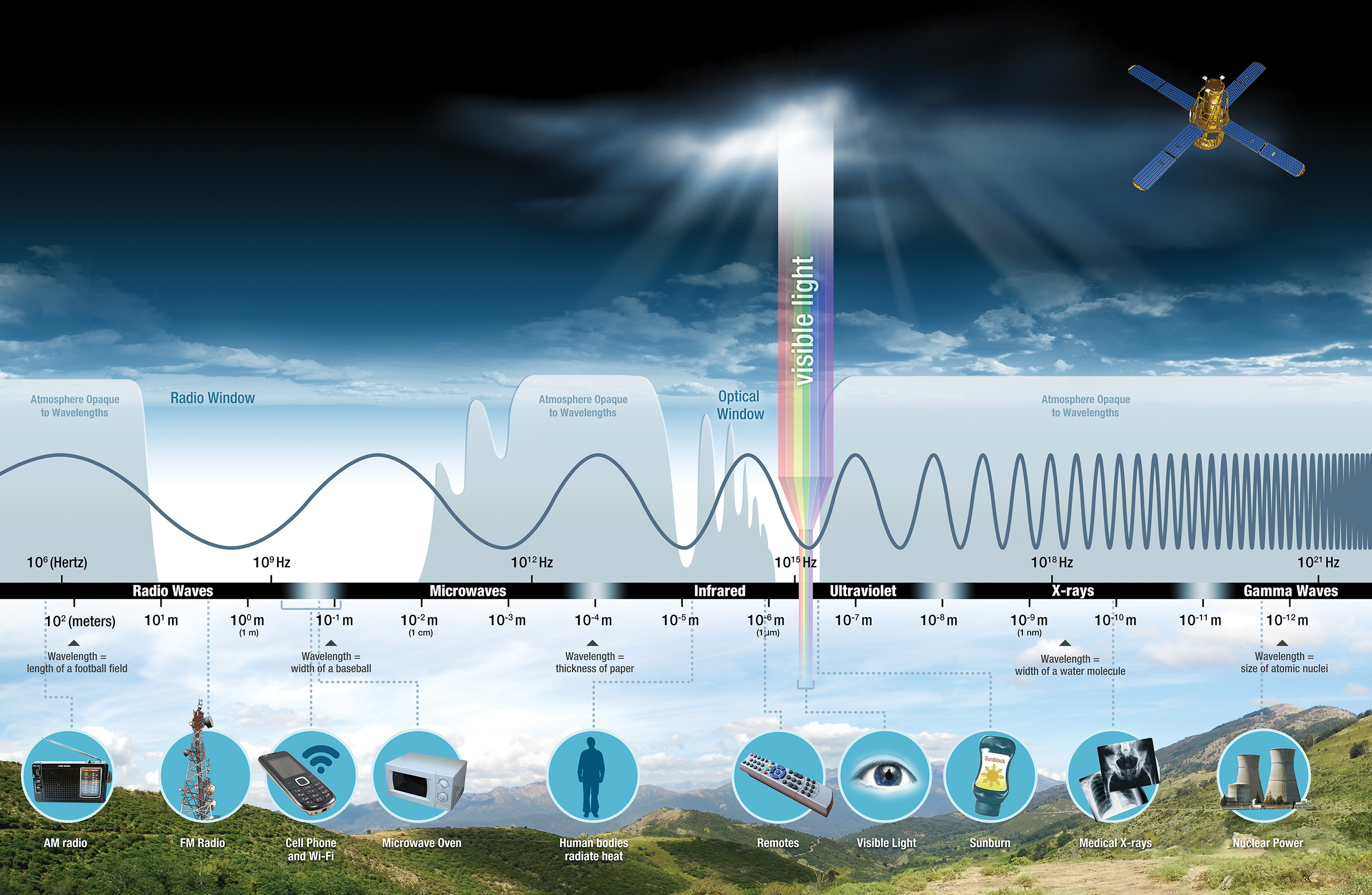

Electromagnetic energy, produced by the vibration of charged particles, travels in the form of waves through the atmosphere and the vacuum of space.

These waves have different wavelengths (the distance from wave crest to wave crest) and frequencies; a shorter wavelength means a higher frequency. Some, like radio, microwave, and infrared waves, have a longer wavelength, while others, such as ultraviolet, x-rays, and gamma rays, have a much shorter wavelength.

Visible light sits in the middle of that range of long to shortwave radiation. This small portion of energy is all that the human eye is able to detect.

Instrumentation is needed to detect all other forms of electromagnetic energy.

Diagram of the Electromagnetic Spectrum. Credit: NASA Science.

Diagram of the Electromagnetic Spectrum. Credit: NASA Science.

Diagram of the Electromagnetic Spectrum. Credit: NASA Science.

For more information on the electromagnetic spectrum, with companion videos, view NASA’s Tour of the Electromagnetic Spectrum.

Sensors

Sensors, or instruments, aboard satellites and aircraft use the Sun as a source of illumination or provide their own source of illumination, measuring energy that is reflected back.

- Sensors that use natural energy from the Sun are called passive sensors

- Sensors that provide their own source of energy are called active sensors.

Diagram of a passive sensor versus an active sensor. Credit: NASA Applied Sciences Remote Sensing Training Program.

Diagram of a passive sensor versus an active sensor. Credit: NASA Applied Sciences Remote Sensing Training Program.

Passive sensor

- Most passive systems used by remote sensing applications operate in the visible, infrared, thermal infrared, and microwave portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. These sensors measure land and sea surface temperature, vegetation properties, cloud and aerosol properties, and other physical attributes.

Most passive sensors cannot penetrate dense cloud cover and thus have limitations observing areas like the tropics where dense cloud cover is frequent.

- Example of passive sensor

Infrared radiation, which can detect heat or thermal radiation from objects or sources;

**Visible radiation, which can capture images or colors of objects or scenes;**

Ultraviolet radiation, which can reveal hidden or fluorescent features or substances;

Temperature sensors that can measure the heat or coldness of objects or environments; sound sensors that can pick up vibrations or noises from objects or sources; and

Magnetic sensors that can measure the strength or direction of magnetic fields or forces.

Active sensor

The majority of active sensors operate in the microwave band of the electromagnetic spectrum, which gives them the ability to penetrate the atmosphere under most conditions. These types of sensors are useful for measuring the vertical profiles of aerosols, forest structure, precipitation and winds, sea surface topography, and ice, among others.

Example of active sensor

Radio waves to detect and track objects in the air, on the ground, or at sea.

Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) utilizes laser pulses to measure distance and create high-resolution maps of the surface or the atmosphere.

Sonar (Sound Navigation and Ranging) relies on sound waves to locate and identify underwater objects or features.

Ultrasound employs ultrasonic waves that can penetrate through solid or liquid materials and produce images or measurements of the internal structure or condition.

Resolution

Resolution can vary depending on the satellite’s orbit and sensor design. There are four types of resolution to consider for any dataset—radiometric, spatial, spectral, and temporal.

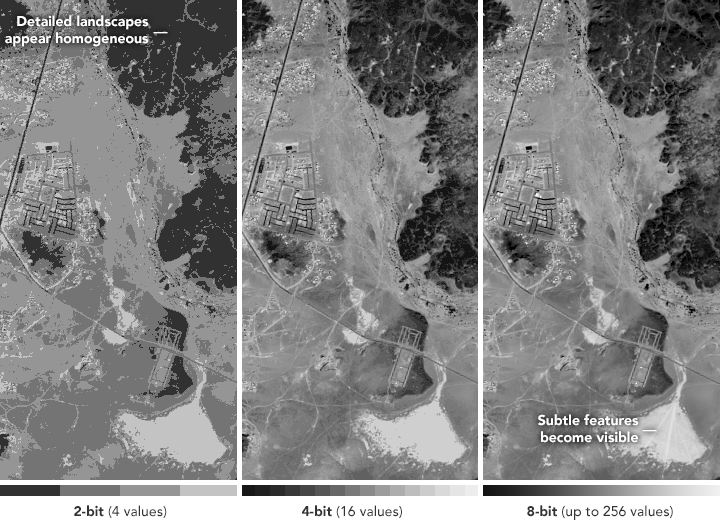

Radiometric resolution

the amount of information in each pixel, that is, the number of bits representing the energy recorded. Each bit records an exponent of power 2. For example, an 8 bit resolution is 2^8, which indicates that the sensor has 256 potential digital values (0-255) to store information. Thus, the higher the radiometric resolution, the more values are available to store information, providing better discrimination between even the slightest differences in energy. For example, when assessing water quality, radiometric resolution is necessary to distinguish between subtle differences in ocean color.

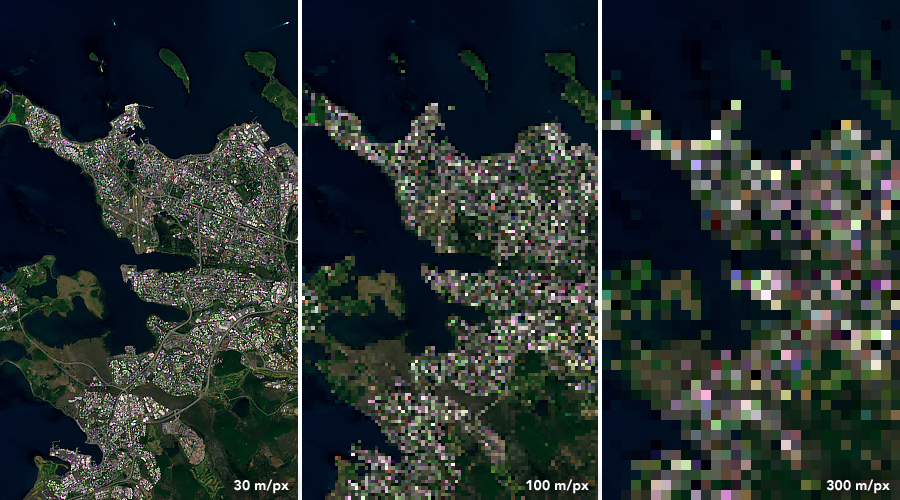

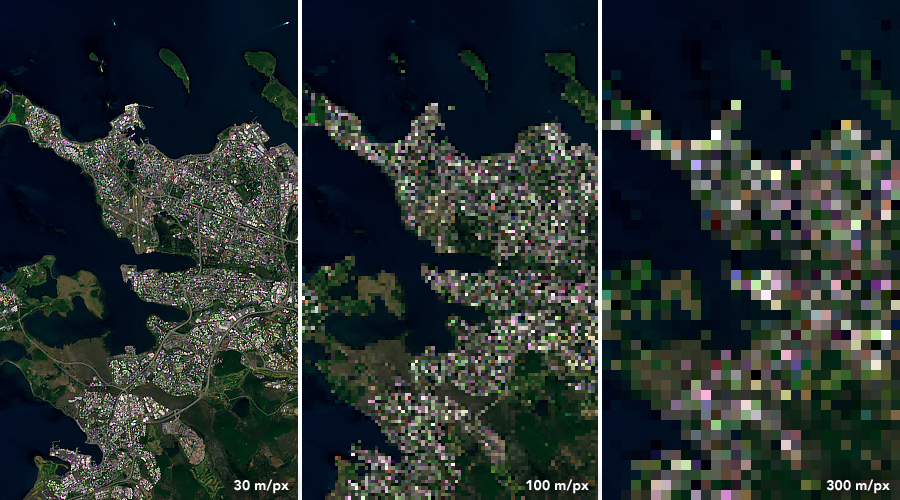

Spatial resolution

defined by the size of each pixel within a digital image and the area on Earth’s surface represented by that pixel. For example, the majority of the bands observed by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) have a spatial resolution of 1km; each pixel represents a 1 km x 1km area on the ground.

Landsat 8 image , illustrating the difference in pixel resolution. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

Landsat 8 image , illustrating the difference in pixel resolution. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory.

Spectral resolution

The ability of a sensor to discern finer wavelengths, that is, having more and narrower bands. Many sensors are considered to be multispectral, meaning they have 3-10 bands. Some sensors have hundreds to even thousands of bands and are considered to be hyperspectral. The narrower the range of wavelengths for a given band, the finer the spectral resolution.

The sides of the cube are slices showing the edges of the top in all 224 of the AVIRIS spectral channels.

The sides of the cube are slices showing the edges of the top in all 224 of the AVIRIS spectral channels.

Temporal resolution

The time it takes for a satellite to complete an orbit and revisit the same observation area. This resolution depends on the orbit, the sensor’s characteristics, and the swath width. Because geostationary satellites match the rate at which Earth is rotating, the temporal resolution is much finer. Polar orbiting satellites have a temporal resolution that can vary from 1 day to 16 days.